Longhouse Theater

UNLOCKING THE SILENCE EXHIBIT

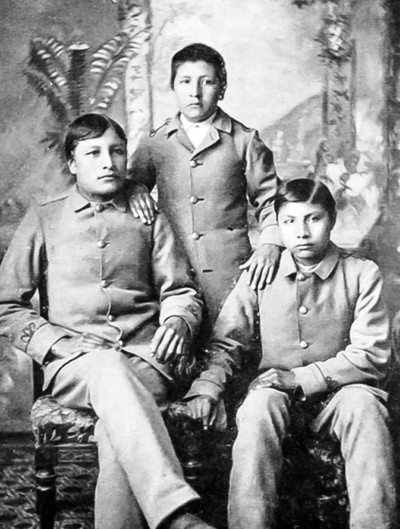

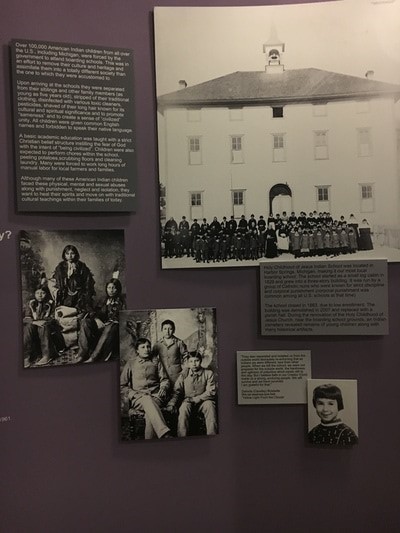

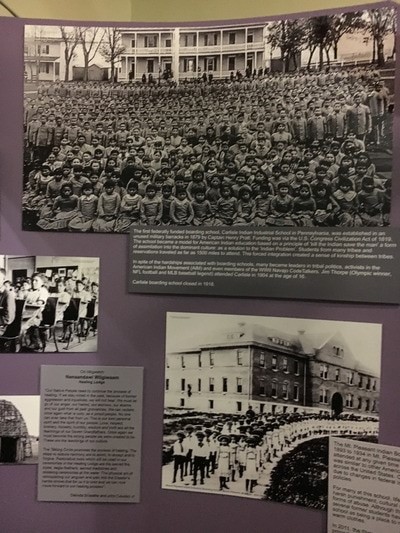

The Holy Childhood of Jesus Indian School was located in Harbor Springs, Michigan, making it our most local boarding school. The school started as a small log cabin in 1829 and grew into a three-story building. It was run by a group of Catholic nuns who were known for strict discipline and corporal punishment (corporal punishment was common among all U.S. schools at the time).

The school closed in 1983, due to low enrollment. The building was demolished in 2007 and replaced with a parish hall. During the renovation of the Holy Childhood of Jesus Church, near the boarding school grounds, an Indian cemetery revealed remains of young children along with many historical artifacts.

We wish to thank Jennifer Devos and Lisa Walker of Gogomain Art, John Causley, DeLinda Brissette, and several Native Elders for their input and artistry.

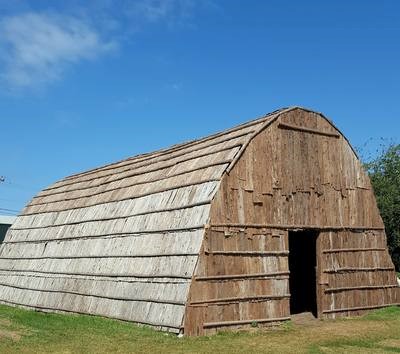

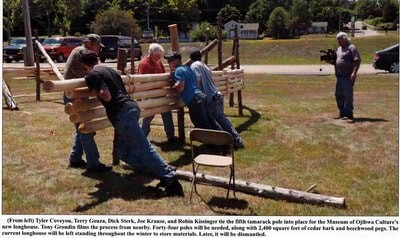

Longhouse / Healing Lodge

Huron Village Longhouses were used by agricultural tribes throughout the Eastern United States. Unlike the Ojibwa's wigwams, longhouses were permanent homes. Home to an entire clan, the longhouse was a symbol of status depending on how long and large the dwelling was. Our Longhouse is much shorter than a historical longhouse of the Huron which would have been around 100 feet in length with 20 feet across. Hearths would be set up every few meters down the longhouse and platforms used as beds along the side walls. The buildings were tall usually around 20 to 30 feet with a long vent for ventilation of hearth smoke. Our longhouse is open to the public to walk through at this time and photos are welcome.

Ojibwa Migration Chart

The Migration Chart is a replication of a birch bark scroll, called a Wiigwaasabak, which recounts the legend around the historical journey of the Ojibwa from their home along the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes and onward to Minnesota which occurred across the 14th and 15th century. The story is rich with good and evil spirits as well as trials that need be overcome. The story focuses primarily on the quest of bear and otter symbolic representatives of the Ojibwa.

“After the Great Manito or God had created all creatures on earth, he found they were dying off and decided he needed to get them to worship him, but he didn't know how so he called a meeting of all the birds and all the creatures on earth to talk about it 'somewhere across the Big Water, where this Manito was. 'The Manito needed someone to take his message to the people and asked who would do it. The Bear was there and said, 'I'll take it across to the people.' The Bear went off with the message of Everlasting Life, but it was very heavy to carry and he could hardly walk. When he came to a wall, he couldn't get through it at first until he stuck his tongue out, which made a hole that he could get through. He did this each time he came to a wall, and the four wind manitos stationed at each of the cardinal directions thanked him for the work he did. He came upon four walls before he finally got through to Midewegun or Mide lodge. The Bear had successfully carried the Pack of Life thus far when he met Megis, the shell, who took over the trek down the St. Lawrence River to Montreal, past the Lachine Rapids to Mattawa, on down the French River to Lake Huron, through the Straits of Mackinac to Sault Ste. Marie. Somewhere along this stretch of the journey, the Megis transferred the Pack of Life to the Otter, who carried it along the south shore of Lake Superior to the Keeweenaw Peninsula, on to LaPointe in Wisconsin, breaking through a sand bar at Fond du Lac at the west end of Lake Superior and traveling up the St. Louis River westward to Leech Lake.” ~As Told By James Red Sky (Eshkwaykeeshik) to Selwyn Dewdney.

The record of the journey by the Ojibwa was in many ways a religious event and creating the scrolls were an activity reserved to a select group in the community who were the only able to write and read them.

Technology and Nature

The Great Lakes region was a wonderful fishing and hunting ground but had harsh winters which meant they needed to use everything around them to survive. This exhibit is divided into three sections; Things from the Earth, Things from Animals and Things from Plants. The Ojibwa often used stone tools. However, when it could be traded, copper was also made into tools and weapons. Pottery was made for storage vessels as well from clay which could be found.

Despite being both hunters and fishermen, the Ojibwa were noted in the Great Lakes for their gill net fishing, the predecessor to modern commercial fishing today. They used every part of the animals that they fished and hunted. Brain was used for tanning, intestines were dried and used as containers, sinew for thread and skin was made into raw hide.

An herbalist of the Ojibwa would have a knowledge of literally hundreds of plants. Edible plants were collected for food and lumber for fuel and housing but also notable was the wide range of medicines and dyes made from foraged plants. The home was lined with birchbark as was the canoe. Sugar was also made from maple sap which was collected annually.

A number of the items in the cases were donated or were made by artisans as they would have been made traditionally. There are also examples of more modern art forms such as quilting which the Ojibwa adopted.

Ojibwa Family Network

Every member of an Ojibwa family contributed to survive. The family was not a nuclear family like today but an extended network from a member's clan, a social system usually composed of relatives rooting from the father's side, which included not just the parents with their children but aunts, uncles, grandparents, cousins and often many adopted members from other tribes as well. Because of the extended network, Ojibwa families were large, usually composed of twenty people. However, it was rare for one couple to have more than three children and not uncommon for siblings to be a decade apart in age. Cousins and adopted siblings usually filled the roles of brothers and sisters, and aunts and uncles filled the roles of mother and father if the need arose.

An 8-minute video with accompanying display shows one example of this type of family. It should be noted that this family does have more children to show what each age group would be expected to do. Children were expected to start contributing at a early age and often married young between 15 and 16. The video explains the roles ranging from an infant to an elder. Many of the people in the video are members of the Ojibwa tribe in St. Ignace and explain some of the roles in a family.

Ojibwa Seasonal Movement

Wigwams were portable because the Ojibwa moved from one home to the next during the seasons. They had specific places where they lived for each time of the year. They lived along the lake in the spring where fishing and wild rice farming was done and moved into the forest in the winter where it was easier to hunt. A circular chart shows where and what was happening to survive in each season.

Currents of Change in the Straits

The last of the exhibits inside the museum focuses on the first contact during the seventeenth century. French fur traders first encountered the Ojibwa of the Straits in the 1620s and for fifty years, the interaction between the two was limited mostly to trade. Fur from beaver was extremely valuable to Europeans but considered undesirable by the Ojibwa which lead to mostly peaceful exchanges. Tensions truly began after the missionaries arrived and were often between the French themselves.

The first display is a lit chart that shows the movements throughout the Straits during the 17th century. It shows the journey of Father Marquette, one of the first and best known missionaries in Michigan and the Beaver Wars and several exoduses from the Iroquois by the Odawa and Huron. The display has brief explanations of each event and labels important locations.

The next display is a wind up chart showing the Huron's, a tribe of the Wendat, who allied with the Ojibwa and their reaction to the fur trade in its busier period after missionary arrival. It is told in first person from the Huron point of view and shows the confusion that often occurred due to a lack of communication and cultural differences.

The last display is broken into two parts: one shows the impact of the missionaries and includes a look at several artifacts from the 17th century and the second half is on how trade changed the way the Ojibwa lived. Pots and pans were traded and beads and fish nets as well. Many items changed the way the Ojibwa dressed, ate, and significantly changed the art styles of the people in the Great Lakes